- Home

- Mark Neilson

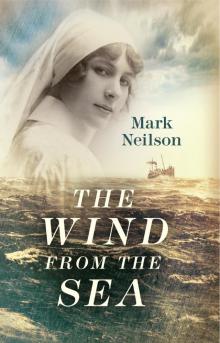

The Wind from the Sea Page 8

The Wind from the Sea Read online

Page 8

He sighed. Then focussed on what he had come to say.

‘Mary. I know you’re under contract until December. But you’ll still be home between the fishings. If you can, I’d like you to drop in to help us when you’re back in Buckie. That job is yours for the taking. I’m seriously thinking of keeping it open for you, until January.’

‘Thanks,’ Mary said awkwardly. ‘I’m happy to help, when I can.’

In the mist beyond the station, a steam engine whistled.

‘Here’s your train,’ said Jonathon. ‘Need a hand with your luggage?’

‘We’ll manage fine,’ said Mary.

The engine steamed out of the mist and ground to a halt at the small station platform. With most of its passengers likely to be picked up nearer Aberdeen, the three girls had it to themselves. Despite their refusal, Jonathon heaved their kitbags, one by one, into their compartment.

As Aggie passed him, he caught her elbow gently.

‘What’s wrong, quine?’ he asked quietly.

He used the word with affection: she heard it as a job, in which other people were wasted. ‘Nothing,’ she answered, snatching her elbow away.

‘Safe trip!’ he called from the platform, as the wheels of the engine spun, and the carriage eased slowly through the clouds of steam.

‘What a nice man,’ Elsie said.

Mary was staring at Aggie. While Aggie looked out at fields she couldn’t see for haar. And a blur of tears.

Something was wrong. And it involved Jonathon. A misunderstanding? Had Aggie found herself falling for him, and drawn back? She knew that Aggie was nowhere near as tough as she seemed. Behind the ready banter, she was vulnerable: still in an emotional turmoil, adjusting to the death of her husband, and the need to work and leave her child behind.

She squeezed Aggie’s work-roughened hand. Whatever it is, I am your friend and I am here for you, that squeeze was meant to say. There was no answer.

Mary stared out of the carriage window at different shades of grey. Here a tree, there a cow, loomed out of the mist and disappeared. Visibility so poor, she couldn’t see the edges of the fields, let alone the sea.

It would be there: it always was.

Her attention turned inward. Something had changed in her over the last two weeks. In early summer, she had travelled this line in the opposite direction trying to put as many miles as possible between herself and nursing. Wanting nothing more than to get home and pick up the threads of the life she had known before.

She was a fisherman’s daughter, and had thought that was enough.

It wasn’t. Not even close. To her surprise, she had loved every minute of the last two weeks. Nursing, organizing, helping Jonathon with the more serious cases that he handled in the cottage hospital. She had felt useful: even fulfilled. Satisfied with every day’s work she put into the place.

There was more to life than being a gutter quine.

She looked blindly out of the carriage window. Was Jonathon right? Did her real calling lie in being a nurse again?

Chapter 5

With the Endeavour gone, the busy harbour seemed empty. Eric dragged an old fish crate to a sheltered corner of the harbour wall: there was an edge to the wind, which spoke of the northern autumn coming. From this wooden throne, he could keep an eye on both sea-bound traffic and the bustling quays beneath the town.

Despite being retired for a year, he hated being left behind. Even if it was by his own choice, because he’d had his day, and now it was up to his sons to make a living from the sea. He reached into his pocket for his tobacco tin.

On the wall behind him, a young seagull was mewling – chased away by its mother and left until hunger forced it to fend for itself. The sound of birds had filled every day of Eric’s life. He barely heard them yet was so attuned to the noise they made that, if it varied, he instantly checked for a reason. As he would for a change in the beat of the engine which had driven his boat.

Like any skipper, he had watched for gulls hovering above the sea, to tell him where the fish were shoaling. Now, even seagulls were struggling in their search for herring. He crumbled the tobacco in his hand, then filled his pipe. This was starting to feel like the seven lean years in Egypt, he thought wryly. The whole town, not just its fishermen, were discovering what it was like to tighten their belts.

His pipe unlit, he rested his hand on his knee. There was a rhythm to life – years of plenty, and the years between. For as long as there had been fishing, it was always thus. You learned to put savings to the side when there was cash to spare: just as you helped others out who were less fortunate than yourself. Widows of fishermen long dead but not forgotten. Or men too old, or ill, to make their own living from the sea. The fishing community made sure that no one was neglected, or went hungry. You looked after each other. It was a way of life.

Eric scrubbed his free hand across his chin. This was changing; he could sense it. The war had stolen a generation of young men, and sent home restless women who had done men’s work in the cities, and were reluctant to go back to the role they had always known.

Once you see life’s alternatives, it can give you itchy feet. For himself, the sea and his family had been enough: he had never bothered to search out alternatives. But the war had forced change – and it wasn’t finished yet. Would the sea heal, then hold, men like Neil? Would the Mary Cowies of the world make a home, settle down to raising a family? Renewing the old place?

Or would too many drift back to the brighter and easier life they had seen, taking away the very people on whom the future of Buckie rested?

What if the herring went too? Once he had thought there were fish in the sea for everyone. Now, he was less sure. Had the war against U-boats destroyed fishing stocks? Had the shoals simply swum elsewhere? Or had he and his kind already emptied the sea, as they tried to keep their boats out of debt, and their families in clothes?

Eric stirred restlessly on the wooden crate, not liking where his thoughts were taking him. If the lean years continued, and the herring stocks failed, then not even those who wanted to stay would find enough work to keep them. What then of his beloved community, and its way of life?

It was the young who would leave, to find work. Taking away themselves, and their children – both born, and still to be born. The community would get older and greyer: less able to look after its own frail and struggling members. A town of old men and women. While the seagulls called and the waves crashed in spray against the harbour, as they had always done.

‘A penny for your thoughts.’

He looked up. It was Chrissie, with Aggie’s little lad in tow.

‘A penny? They’re not worth even half of that,’ he muttered.

‘They were deep enough to make you forget your pipe.’

‘Aye,’ Eric said. His hand went straight to his left pocket for his box of matches. ‘Will things ever get back to how they were, Chrissie? Will the town get back to what it was before the war? Will Andy and Neil ever settle down, and bring up their families here? Like you and me once did. Or is it all going to change?’

‘Michtie me!’ she said wryly. ‘These are black thoughts for any man.’

He struck his match, held it over the bowl of his pipe, and puffed. ‘Aye, but it’s happening, isn’t it? Everything we knew is under threat. If the fishing industry dies, there’s not a store in town that doesn’t live on ships’ orders for ropes, and coal, and provisions. And there’s not another shop in town that doesn’t draw its living from the families of the lads out fishing. If fishing goes, what will happen to the town? To folk, looking after weaker folk, as they did before us and as we do now? Can you tell me that, Chrissie?’

She studied him. There’s a danger, when you have known someone all your life, that you see him as he was in his prime. Not as he is. But Eric was still a fit and able man. Having left the sea to make way for his sons, rather than because he couldn’t cope with it any more. Now restless in his new-found idleness. A man who had stoppe

d working too soon.

‘Of course everything’s changing, Eric,’ she said. ‘Nothing stands still. If it did, we would all turn into stone.’

‘Is it changing for the better?’

‘The young think it is. It’s only old folk like us who look back to the past.’

‘Mmphm.’ He took the pipe from his mouth. It had gone out again. Almost as if he had lost the heart to puff at it.

Chrissie read his mind. ‘It’s a poultice you’re needing to put on the back of your neck, to draw that pipe,’ she scolded. ‘But I have the very cure for you.’

‘What’s that?’ he asked.

‘Come back, and I’ll make you a cup of tea,’ she said. ‘Have you had your breakfast yet?’

Eric shook his head. ‘No, I forgot. I came down to help the loons cast off.’

‘Well, there you are!’ she said triumphantly. ‘I never knew a man yet who could talk sense on an empty stomach.’

‘It’s my turn to clean the hut and cook,’ Aggie said.

‘I’ll help,’ Mary offered.

‘No need. Go up to the town with the others. It’s the weekend.’

All of this without eye contact. This was not the Aggie she had known and worked with for years. Something was badly wrong, but Mary was unsure how to tackle it. Clearly, her company wasn’t wanted – but there were other priorities. Like trying to get to the bottom of Aggie’s problem, and put things right.

She picked up the brush, and began to sweep the floor.

‘I can do that!’ Aggie said crossly. ‘I told you, it’s my turn.’

‘I heard you.’

Mary kept on sweeping. She felt her friend’s irritation rise, then ebb. Now. If there was a time to strike, this was it.

She stopped working. ‘What’s up, Aggie? What’s the problem between us?’

‘Nothing’s up. There isn’t a problem.’

Aggie banged the dirty pots and pans around, as she cleared the area round the well-chipped kitchen sink.

‘These last three days, you’ve scarcely said a word.’

‘You’re imagining things.’

The dirty pots took another beating.

‘Even Gus has asked what’s wrong.’ Mary turned, to see Aggie leaning on closed fists at the kitchen sink, her head bowed. Quietly, she set the brush aside, then walked over to her friend.

Aggie turned her face away.

‘You’re the best friend I’ve got,’ said Mary. ‘What’s wrong?’

Aggie blindly shook her head.

‘There must be something.’ Gently, Mary pulled her friend round. Aggie’s face was wet with tears. ‘Oh, Aggie! Tell me what’s wrong.’

Somehow, they had their arms round each other, Aggie’s shoulders shaking like a child who thinks the whole world has turned against her. Mary held her tight, until the sobbing eased. Then Aggie pushed her away, but gently.

‘It’s my own fault,’ she said, her voice choked.

‘What is?’

‘A widow woman – thinking about another man. I feel guilty … I feel angry … I don’t know what I feel.’

‘What other man? And why not? You have your whole life in front of you … you’re young, yet. You can’t just lock yourself away. Tom wouldn’t have wanted you to do that.’

‘It’s just …’ Aggie started. ‘He’s been so good with wee Tommy. So patient, so easy with him.’

Jonathon! Who else? Mary had guessed right when she sensed that something had gone wrong between the two of them at the railway station.

‘I took a friendship,’ Aggie said. ‘And tried to turn it into something else … something it was never meant to be. I got ahead of myself, that’s all. Now I’ve probably messed up everything.’

‘With Jonathon? Never. I doubt he even knows what’s gone on.’

Aggie shook her head. ‘Not him,’ she said. ‘He’s too decent a man. It was all me. Adding two and two and getting twenty-five.’

Mary frowned. ‘Why not Jonathon?’ she demanded. ‘The two of you have been as thick as thieves for years.’

Aggie stared at her. Let silence build.

‘Well, you have,’ Mary said, defiantly.

‘Maybe,’ said Aggie. ‘But now, all he can talk about is you. “Mary did this, Mary said that, Mary dropped in and saved the world …”’

Mary stood stricken. ‘But I didn’t know,’ she finally said. ‘All I was trying to do was help him out when he was short of a nurse. When he offered me the job, I was as surprised as you.’

Wind moaned round the corners and found the cracks in the ancient wooden hut. Cracks which other quines in other years had stuffed with newspapers, now stained and faded into unreadable print.

‘So that’s what was wrong?’ Mary asked quietly.

Aggie nodded.

Mary reached out and took a firm grasp of her friend. ‘But, Aggie. I don’t want your Jonathon. Right now, I don’t want any man. I’m in as big an emotional mess as you. I don’t know what to do with my life. I don’t know whether I want to stay here and settle down. Or go back to nursing. I’m so confused.’

Aggie screwed up her handkerchief into a tiny, sodden ball, her eyes on the floor. They came slowly up to meet Mary’s.

Mary shook her gently. ‘Whatever happens, I don’t want to lose our friendship.’ Then she blinked. ‘I know. When we get back home, why don’t you come up to the hospital with me? Help out with the nursing work. I’ll show you how to make the beds, lift the patients. Most of nursing is only doing what you do already with wee Tommy. Common sense. Being a mother to everybody.’

‘I couldn’t,’ Aggie started.

‘Why not?’

‘The Wee Man. The only time I’ve got with him is when we’re in Buckie.’

‘Then work part time. Look, if you want to show Jonathon that you can do more than hold a gutting knife, here’s your chance. He’s desperately short of nurses. I can teach you within days to be a better nurse than the lazy lump he has there. What do you say? Are you willing to try?’

A glint came back into Aggie’s reddened eyes. ‘And you can show me?’

‘Like other nurses once showed me.’

Aggie pushed her away. ‘Right, quine,’ she said. ‘Get on with that sweeping. I’ll run the pots and dishes through. If we put our backs into it, we can nip up and have a look at the Union Street shops, before I start the dinner. Come on!’

‘It’s a deal,’ said Mary, reaching for the brush.

The paraffin lantern swung on its hook, and the ship’s timbers creaked. The net had been shot and the crew were grabbing some sleep before hauling it. The engine was silent, only the small stern sail working, giving the ship enough steerage way to control the rate and direction of her drift.

Neil hunched over the school jotter, his pencil busy. Sketching Andy’s face, relaxed in sleep. The burden of command had already etched some lines on it, and there was a small frown beneath the tumble of dark hair over his brow.

The brown rat appeared silently and suddenly on the table top. These fishing boats were full of vermin, no matter how many the crews caught and killed. With all the fish guts scattered and rotting around the harbours, docklands were Rat City and their inhabitants adept at climbing mooring ropes and colonizing boats.

The rat’s nose twitched, its beady eyes on Neil. The nose assessing the half-eaten sandwich on the table. No mathematician could have done a quicker or more accurate sum on the balance of risk.

Neil saw the beast from the corner of his eye. Watched quietly, and with a touch of humour. The rat eased towards the sandwich, flowing smoothly and silently in the shadows cast by the lantern above. It reached its goal, and paused, checking again. Neil kept up the steady scratching of his pencil.

The rat sniffed the bread, then the uneaten cheese which filled it. It looked sharply at Neil, ready to flee at the slightest movement. Rat and man watched each other stealthily. The rat put its paws on the edge of protruding cheese, and began to nibble.

&nb

sp; As Neil began to sketch, on a corner of his page. Barely moving his eyes to take in his subject, which was making inroads into the cheese, while watching him throughout. It was Neil’s sandwich. Left lying there because he wasn’t hungry, and dared not go to sleep. He was glad to see it find a properly appreciative home.

On the page, the rat’s head and shoulders emerged, the almost human tiny hands. The whole image vibrating with the electric tension of the real rat.

His pencil scratched on. Live, and let live, Neil thought. Out in the trenches, he had got used to the rats running over his sleeping – or sleepless – face. This, in the quiet creaking and gentle movement of the boat, was better.

Infinitely better.

Mary smiled. He was sitting on a rusting bollard in the harbour, head tilted back, watching white clouds scamper across the sky. Wondering how to draw them and show their movement, she was prepared to bet.

‘Are bollards all you can afford?’ she asked his back.

‘Mary Cowie,’ he said, and there was a smile in his voice. He spun on the bollard and rose smoothly to his feet. ‘I would know that voice anywhere.’

The sea had tanned his face, she thought. Given him back his confidence.

‘You were watching the sky,’ she accused, ‘and wondering how to draw these clouds with the sun behind them.’

‘Guilty as charged. Why aren’t you up in the town, laughing at the new Chaplin film with the other quines?’

‘I didn’t feel much like laughing,’ Mary said.

The good-humoured grey/green eyes sharpened. For a second, she felt they were looking deep inside her. She shivered, turning her head away, to stare over the forest of masts, where half the drifters in the world were moored. Only Yarmouth would have more boats in harbour.

‘When did you leave Peterhead?’ she asked.

‘We got here this morning. You have a problem that’s bothering you?’

The Wind from the Sea

The Wind from the Sea